Day 4 - Geological Background

INTRODUCTION TO THE KEM KEM AND AKRABOU FORMATIONS

Surrounding the Palaeozoic window of Tafilalt of southeastern Morocco (palaeontologically famous for its diverse trilobites, among many other fossils groups) is a series of mid - Cretaceous strata that records a transgression from fluvial facies Albian - Cenomanian Kem Kem beds to platform carbonates of the Late Cenomanian-Turonian Akrabou Formation. Both of these stratigraphic units are well known for their fossil vertebrates, and in both formations the fossils are mined commercially and sold around the world. We will examine both of these stratigraphic units and be provided with opportunities to talk with the people who dig the often remarkable fossils.

The age of this transgressive sequence of strata coincides with the separation of South America and Africa during the opening of the South and Central Atlantic Oceans. There are similarities between, for example, the vertebrate assemblage of the Kem Kem beds and the Crato and Santana formations of north east Brazil. Freshwater fishes of the Kem Kem, including ichthyodectids such as Cladocyclus, the amiiform Calamopleurus and the coelacanth Mawsonia occur in both Morocco and Brazil. But there are important differences too. The elasmobranch Onchopristis, so abundant in the Kem Kem beds has yet to be recorded from South America. There are terrestrial tetrapods common to Morocco and Brazil that suggest a land connection between the two continents was persistent. The huge African theropod dinosaur Spinosaurus and the Brazilian Oxalaia are indistinguishable, and are probably congeneric. Indeed, the holotype of Oxalaia quilombensis is so remarkably similar to Spinosaurus moroccanus that they may even be conspecific.

In the marine Akrabou Formation the fish assemblage also has similarities with fishes from the Brazilian Santana Formation, although it is nowhere near as diverse as the Brazilian ichthyofauna. Araripichthys and Cladocyclus appear to be taxa common to both formations, and a newly described ray Tingitanius has affinities with the Brazilian Iansan. However, the differences are considerably more marked than the similarities. The Akrabou Formation yields plesiosaurs and agialosaurs, both unknown from the Santana Formation. In addition, the Akrabou Formation is rich in fully marine invertebrates including ammonites, which again are unknown in the Santana Formation. Palaeoenvironmental conditions can account for some of these differences, but it is highly likely that distinct faunaI provinciality had begun to develop between South America and North Africa by late Albian/early Cenomanian times.

In addition to these Cretaceous localities, we will also examine some of the famous Palaeozoic localities that yield spectacular trilobites, crinoids and of course, some amazing Devonian fishes, including placoderms and early elasmobranchs.

TECTONIC SETTING OF THE KEM KEM BEDS

The Mesozoic and Cenozoic deposits of South eastern Morocco span a time interval from the Albian ?-Cenomanian to the Plio-Quaternary and form part of the 'Plateforme Pré-Africaine', (Ferrandini et al. 1985, Zouhri et al. 2008). Cretaceous outcrops are well visible as steep escarpments, while many tertiary deposits are also exposed, due to the uplift of the atlas system (Zouhri et al. 2008). Rifting and faulting episodes, in combination with eustatic highs largely influenced sedimentation during Cretaceous-Cenozoic times in the Sahara domain (Zouhri et al. 2008).

The Cretaceous-Tertiary deposits are part of the Hamada domain and form an angular discordance on a

palaeozoic base. This domain is delimited to the South by Ougarta, to the East by the Hamada du Guir, to the West by the Draa Hamada and to the North by the eastern Anti Atlas, via the Anti Atlas major fault ('accident majeur de l'anti atlas' (see figure 11a, Choubert 1945, Zouhri et al. 2008). It is important to note however, that these limits are quite arbitrary, mostly based on the lateral evolution of fascies, which usually follow pre-Cretaceous appalachian reliefs.

The Hamadas in South Eastern Morocco do not seem to contain Triassic, Jurassic or Lower Cretaceous

deposits because the eastern Anti Atlas is located on the shoulder of the Atlas rift zone (Baidder 2007, Malusa et al. 2007). This shoulder was eroded in the Late Jurassic and likely fed the red beds in the High Atlas.

In the North, close to Errachidia and south of the Atlas Fault, the Hamada System is first visible and three main hamadas are distinguished (Zouhri et al. 2008): the Hamada of Meski, also known as Hamada of Meski-Aoufous, the Hamada of Boudenib and the Hamada du Guir (figures 2 and 3). Sediments found in the Hamada of Meski escarpement, mostly reddish sand and siltstones with gypsum, may be lateral equivalents of the Kem Kem sequence, but could also represent older layers of the 'infracenomanien'. Folds on the Hamada are orientated E to W. This is where the Triassic boundary is located, established through the discovery of lagoonar gypsum deposits dated to the Lias (known as the Gulf of Aoufous) (Frison de la Motte 2008). This coincides with the limit of the South Meseta Fault Zone (Michard et al. 2010, in press). The escarpment of the Hamada of Boudenib on the other hand contains argilaceous redbeds younger than the Turonian. These are topped by Miocene limestones (Zouhri et al. 2008).

In the Guir Hamada continental Miocene deposits are generally topped by limestones and conglomerates, possibly of Pliocene age. Further south however, these Mio-Pliocene sediments lie on top of Cretaceous redbeds (Tafilalt Taouz map by Destombes and Hollard, 1986). In the Kem Kem area these Cretaceous and Miocene-Pliocene formations can be seen again and are well developped, providing evidence for regional deformation of the atlasic basement and its Mesozoic cover during the Neogene phase of the Atlas Orogeny (Zouhri et al. 2008). Unconformities between the red beds and the plateaus show evidence for syntectonic sedimentation at the southern rim of the uprising Atlas belt (Zouhri et al. 2008) which has already started by the Late Cretaceous (Frizon de la Motte 2008).

The Draa Hamada, which is part of the same system as the Guir Hamada (Grandes Hamada system) consists of poorly dated Cenozoic continental deposits, overlaid by Quaternary formations. Cretaceous sediments, including the Cenomano Turonian limestone platform, do however also occur, in the west of this basin (Zouhri et al. 2008). It is important to note here that the extent of the overlying Cenomanian-Turonian limestone platform retraces the major paleogeographical traits of the Moroccan coastline (Choubert 1943, 1948). The outline of the limestone platform in turn was largely a consequence of the opening of large faults in early Aptian times: the continental fracturation and thermal relaxation defined the outline of the Cenomano-Turonian transgression on the Meseta (Zouhri et al. 2008).

While the South Atlasic fault (Michard et al. 2008), which shows reliefs of alpine type and delimits the High Atlas is well known and studied (Frizon de la Motte et al. 2008), the fault system it created in South Eastern Morocco has only recently been studied in more detail (Baidder 2007, 2008). A complex system of faults has been identified north of the Kem Kem Hamada, the two most important ones being the Erfoud and Taouz faults. The southern fault is the only one with an official name (Omjrane - Taouz fault) and is a branch of the major Anti Atlas fault. The 'Erfoud fault line' on the other hand runs from Erfoud through Jorf in Morocco and all the way to Jorf-Torba, near Bechar in Western Algeria. Together, these two faults delimit the Tafilalt to the North and South. The effect of these fault lines is still felt today, as for example in the Rissani earthquakes of October 1992, which occurred at a depth of approximately 14 km (Hahou et al., 2003) and five of which reached magnitudes of 3.3-4.0.

The basic tectonic setting of the Kem Kem also seems to affect the distribution of fossil rich localities. Field observations of the two 2008 expeditions show an interesting pattern in the distribution of fossil sites. Most sites are located in synclinal structures, suggesting that rivers flew through soft lithologies, such as Carboniferous deposits in Aferdou N'Chaft and lferda N'Ahouar, paralleling synclines and flowing in a general North-South direction (Baidder pers com). The Gara Sbaa exposures represent a notable exception, but were also laid down in soft Silurian lithologies between the Ordovician sandstone and Devonian limestone.

PALEOENVIRONMENTS OF THE KEM KEM BEDS

The Kem Kem beds as a deltaic river system

The preservation, sedimentological context and taxonomy of Kem Kem fossils indicate that the vast majority of them were deposited in a fluvial environment. Sereno et al. (1996) proposed a deltaic setting for the Kem Kem beds, and this interpretation is certainly the most accurate published to date. However, the fluvial system is not well understood (Ibrahim et al. 2010) and not all localities necessarily record rivers or river-like environments: lake-like deposits for example have also been identified (Dutheil 1999, this study, Sereno pers. com. to Ibrahim). The Boumerade locality for example seems to record a fossil vertebrate assemblage deposited in a low energy, freshwater environment, most probably a lake. Fossil elements collected there show little evidence of transport and only a small number of elements from Boumerade are unidentifiable.

The fluvial system included large rivers, all flowing in a northerly direction. Russell's (1996) proposition that the environment of this part of the sequence was likely a fluvial plain with westward drainage is incorrect, as all measurements strongly suggest a N and NE flow direction. It is also noteworthy that a number of physical barriers such as the 'Massif de Loubnat' and the Saghro reliefs caused by the Atlasian uplift (Malusa et al., 2007), may have geographically restricted vertebrates in the Kem Kem region to some extent. Similar geographical barriers are thought to have limited gene flow between Cenomanian dinosaur faunas in Niger and Morocco (Sereno and Brusatte 2008) .

PALAEOENVIRONMENT AND CLIMATE OF CENOMANIAN NORTH AFRICA

Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia were part of a transition zone between continental masses and the nearby marine environments from the end of the Paleozoic to the early Late Cretaceous (LeFranc and Guiraud 1990). According to Delfaud and Zellouf (1995), the Kem Kem sequence represents the northern part of the Paleo-Niger River that crossed the western Sahara before and after the opening of the Atlantic. It may thus be the equivalent of the paleo-Nile, which discharges into the sea at Bahariya. The Kem Kem probably discharged into the ocean in a N-N-E direction.

It is very likely that the planet experienced extreme hothouse conditions in the 'mid' Cretaceous, a conclusion strongly supported by the presence of temperate forests inside the Arctic and Antarctic circles (e.g. Herman and Spicer 1996; Falcon-Lang et al. 2001), and extremely high sea surface temperatures (Boucot and Gray 2001). These hothouse conditions may have been particularly severe in localities located in today's Saharan environment (Russel and Paesler 2004). Whether some adaptations of Saharan dinosaurs, such as the high dorsal spines of the Kem Kem taxa Spinosaurus and Rebbachisaurus, and the older (Aptian) taxa Ouranosaurus and Suchomimus from Niger were adaptations to climatic conditions is not clear.

The presence of large rivers and waterbodies in the Kem Kem sequence, and especially the presence of a large freshwater vertebrate community serve as reminders that, while warm and possibly arid overall, the Kem Kem delta was a zone of high biodiversity and an extremely productive environment. A modern, albeit smaller, equivalent might be the Sao Francisco river in Brazil, which flows through largely arid terrain but allows a rich and diverse ecosystem to flourish on its banks.

In the case of the Kem Kem, a virtually constant supply of fresh water was necessary to provide living conditions for the abundant crocodyliforms and turtles, which unlike some fish, generally do not migrate long distances. Evidence from the Boumerade locality, where occasionaly highly mixed assemblages are found, suggest that flooding events did occur, accumulating fossil material from the entire plain.

THE KEM KEM BEDS OF BEGAA

A dinosaur-tooth mine in the Cretaceous Kem Kem beds of Begaa.

A dinosaur tooth fossil shop deep in the Sahara Desert. The dodgy looking character in the woolly

hat is Dr Longrich of Bath University.

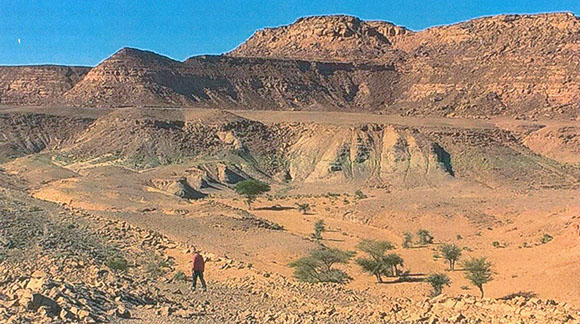

The Kem Kem Plateau, here an isolated inselberg shows the complete sequence of Kem Kem beds

resting on lower Palaeozoic clays (probably Silurian) between Er Remlia and Taouz.

Vertebrate remains occur in the top middle third of the section. The top of the plateau is

limestones of the Cenomanian-Turonian Akrabou Formation.

FOSSILS OF THE KEM KEM BEDS

Spinosaurus

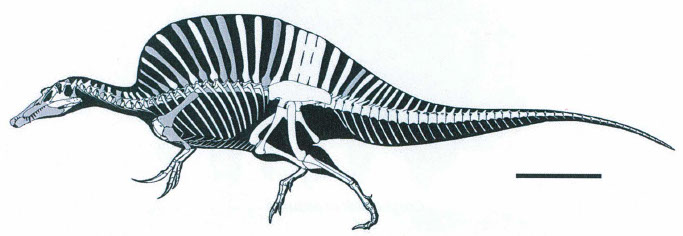

An outline of the skeleton of Spinosaurus. Possibly the longest of all the Theropoda

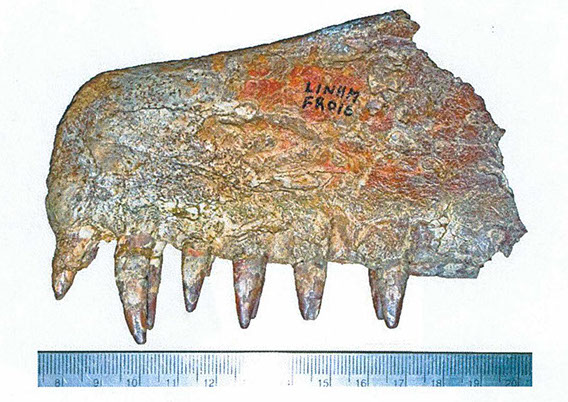

Carcharadontosaurus

Anterior ornithocheirid pterosaur tooth

Posterior ornithocheirid pterosaur tooth

These teeth are probably from Coloborhynchus or Siroccopteryx. The former is known from Brazil and

England, the latter has only been recorded from Morocco.

Left lateral view of Siroccopteryx rostrum. Notice that only the third tooth form the front is

curved (the first tooth is not visible as it projects from the front of the rostrum. In this

specimen it is broken (see figure below)).

Dorsal view of the rostrum of

Siroccopteryx holotype specimen.

Anterior view of rostrum of Siroccopteryx.

-------------------------------------------------------------

CROCODILES FROM THE KEM KEM

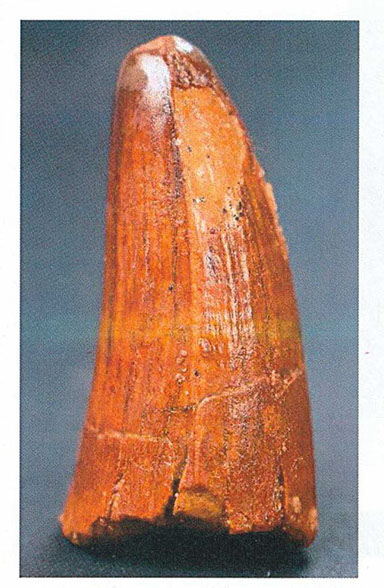

Short stubby teeth like this are probably from Elosuchus.

The really stubby ones are from the back

of the jaws

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

SHARKS FROM THE KEM KEM

Perhas surprisingly for a fluvial deposit, the Kem Kem beds contain quite a high diversity of sharks and rays.' The fins spines of hybodonts occur frequently, although the teeth of these sharks are rare. There are two morphs: one fins spine has long ribs on the fin spine, like the genus Hybodus. This form may belong to Tribodus, better known from Brazil. A second morph has small denticles on the fin spine sides, and is similar to the Jurassic Asteracanthus, but no Asteracanthus teeth have been encountered.

The rostral 'teeth' of the saw shark Onchopristis numidus are very common in the Kem Kem, and some

indicate that this saw shark reached very large sizes. The rostra of this large saw shark are occasionally encountered also.

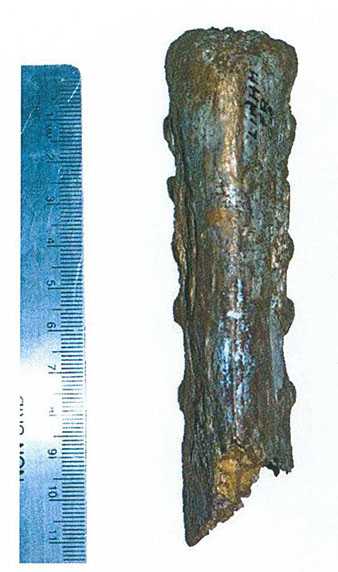

Hybodont sharks

Hybodont finspine with fine ribs.

Hybodont finspine with coarse ribs.

Onchopristis: a saw shark

This common fossil in the Kem Kem is a rostral 'tooth' from the saw shark Onchopristis numidu s.

A partial rostrum of Onchopristis with 'teeth' of various sizes.

Lamniforms

Although rare, the teeth of lamniform sharks, more typically found open marine conditions, also

occur in the Kem Kem beds.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

BONY FISHES OF THE KEM KEM

The Kem Kem is rich in bony fishes. The most frequently encountered remains are the ornamented skull bones of the large coelacanth Mawsonia gigas, the unmistakable teeth of lungfishes, and shiny scales of lepidotids. There are many other fish remains, but they occur less commonly. The fish assemblage contains a mix of 'primitive' forms and modern forms. The amiaform Calamopleurus is very close to the Brazilian specie from the Santana Formation. Also, as in the Santana Formation, there is a Kem Kem species of Cladocylcus.

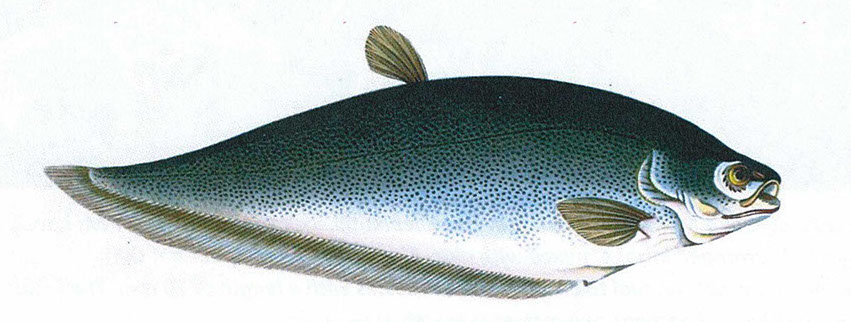

For many years the fossil diggers discovered subcircular bony plates that no one seemed to know what they were. These were collected and sold as curios. Eventually a skull was discovered with the plates, and it was realised that they were highly modified teeth of an osteoglossomorph fish called Palaeonotopterus. The name means ancient southern fin.

Today, the extant osteoglossomorph (the related knife fish), Notopterus notopterus lives in South Asia.

These strange plates are teeth of the osteoglossomorph Palaeonotopterus. They were used for crushing molluscs. Scale bar 30 mm.

A super example of a Moroccan fake fossil. These lepidotid scales form the Kem Kem have been carefully arranged in sand, mixed with glue. The fossils are real, but not the arrangement. It is not unusual to encounter these scales with a length of 70 mm. They must be from individuals of perhaps two metres in length.

---------------------------------------------------------------

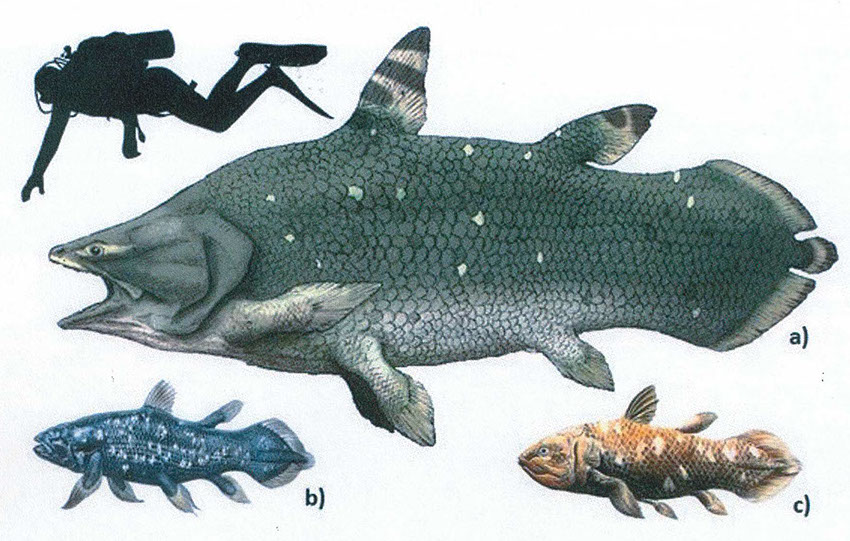

THE KEM KEM COELACANTH: MAWSONIA GIGAS

Just for scale, an anachronistic diver (top-like you didn't work that out), Mawsonia gigas (centre) and the two extant species of Latimeria (bottom).

-------------------------------------------------------------

LUNGFISH

Teeth of the lungfish Ceratodus.

Introduction

Arrival

Day 1

Day 2

Day 3

Day 4

Day 5

Day 6