Wednesday 28th August 2013

We spent two days in the Bungle Bungles or Purnululu as it is known to the locals. The first day we concentrated on the northern part of the park with a late afternoon drive to look at the southern bit.

Like all Western Australian parks it is theoretically completely open, but in reality you are directed to restricted portions. These bits, however, are (I think) the best bits.

The southern portion is where you find the world famous stripy domes – the northern part is slot canyons.

The Geology of the Bungles is Devonian sandstone, as you can see in the following map.

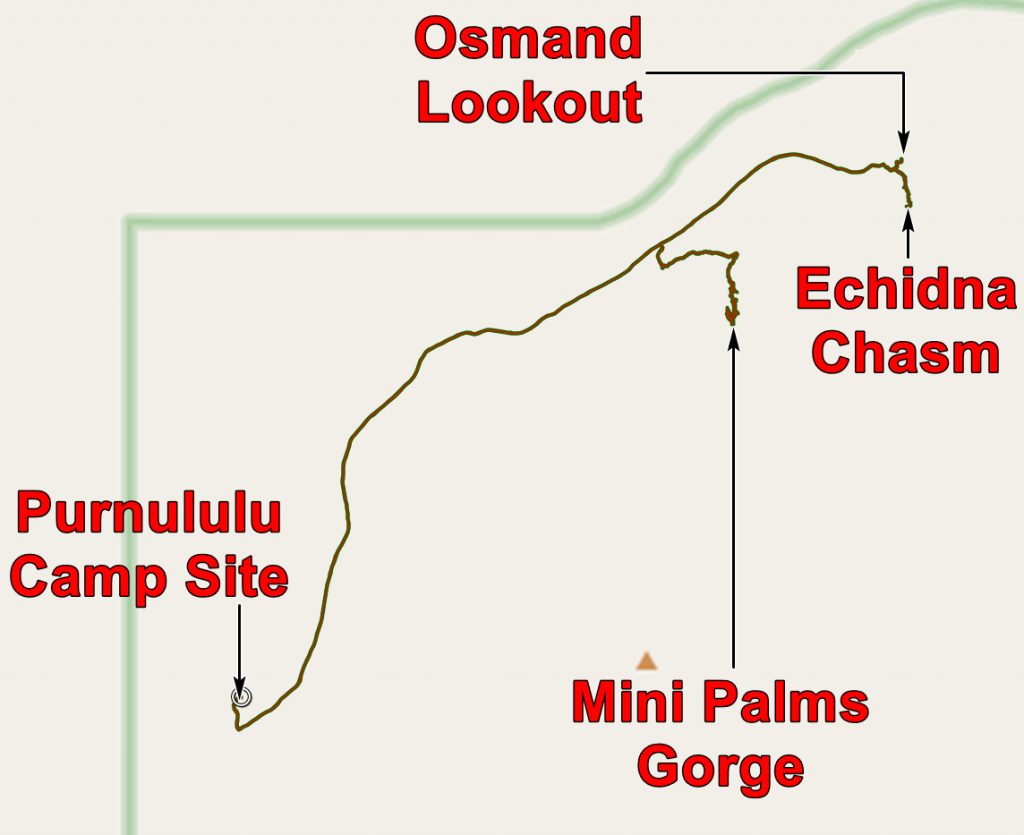

The route we took on this day can be seen on this extract from the geological map.

You can see that there is a meteorite impact structure in the centre of the Bungle Bungles. Seeing it on this map was the first that I became aware of it! I did not notice any evidence for it on our visit to the Bungles. You can read a bit more about it HERE. It must be younger than the Devonian – probably not very much younger as it has been much eroded.

But back to the slot canyons. We drove north to the car park, looked at the informative signs and decided on our plan. The first we went in was Mini Palms Gorge, named after the Livistona palms which are found in the gorge.

Livistona Palms on the Mini Palms trail

At first the gorge is fairly open but the fallen rocks can make progress a bit of a squeeze. As you can see the rocks are mainly coarse conglomerate

Chris making her way along the Mini Palms Trail

At the end of the gorge there is a viewing platform from which the amphitheatre can be seen.

Chris continues to make her way along the Mini Palms Trail

The amphitheatre at the end of Mini Palms Gorge

Coming down from the top of the gorge is a long cascade of ferns.

Ferns cascading from the rim of the gorge

We then drove a little further north and walked into Echidna Gorge. I understand that echidnas are anteaters and likely to be found on the plains – not in the confines of a gorge. And once in the gorge you certainly are confined!

Entering Echidna Gorge, where it is still wide enough to have vegetation

As you go further in the walls become closer together and vegetation disappears. When the stream which cuts the gorge is flowing I do not think this would be a place to be. The gorge follows joints which do not appear to be faults. Presumably they formed when the rock became less pressurised as erosion brought it closer to the earth’s surface – remember the impact structure of which we only see the deeper parts.

Following a stream eroded joint- I think vertical erosion is stronger than horizontal here!

One feels rather small

The chasm gets narrower.

Chris in the chasm. I wonder how high the water gets in a thunderstorm?

Because the gorge is so narrow sunlight is not able to flood it – there are always walls in shadow and some in light.

Light and shade in the gorge

After a unique walk, taking us into one of the strangest places we had ever been, we turned and walked out.

Chris walking out of Echidna Gorge

At the entrance to the chasm we walked to the Osmand Lookout to look across to the Osmand Range which contain permanent waterholes and pockets of rainforest. Access is restricted as there are some very rare plant and animal species.

The Osmand Range – folded Protozoic sediments containing permanent water courses.

As we returned to the car park we met a bus load of people making their way into the gorge. Some looked super-fit and others a lot less fit. And a group leader looking worried. It must be very difficult to keep all happy in a situation like that, especially when you consider the cost of these tours.

We lunched at our camp and then headed south. I will talk about that in the next post.

The application below shows you various .kmz files. If you open them with Google Earth you will get our route and the photographs I took, at the spot I took them, displayed in all their glory! Download the file you want, store it somewhere on your computer, open Google Earth and open the file.

[slickr-flickr tag=”28-08-13-1″]