Monday 30th September to Wednesday 2nd October 2013

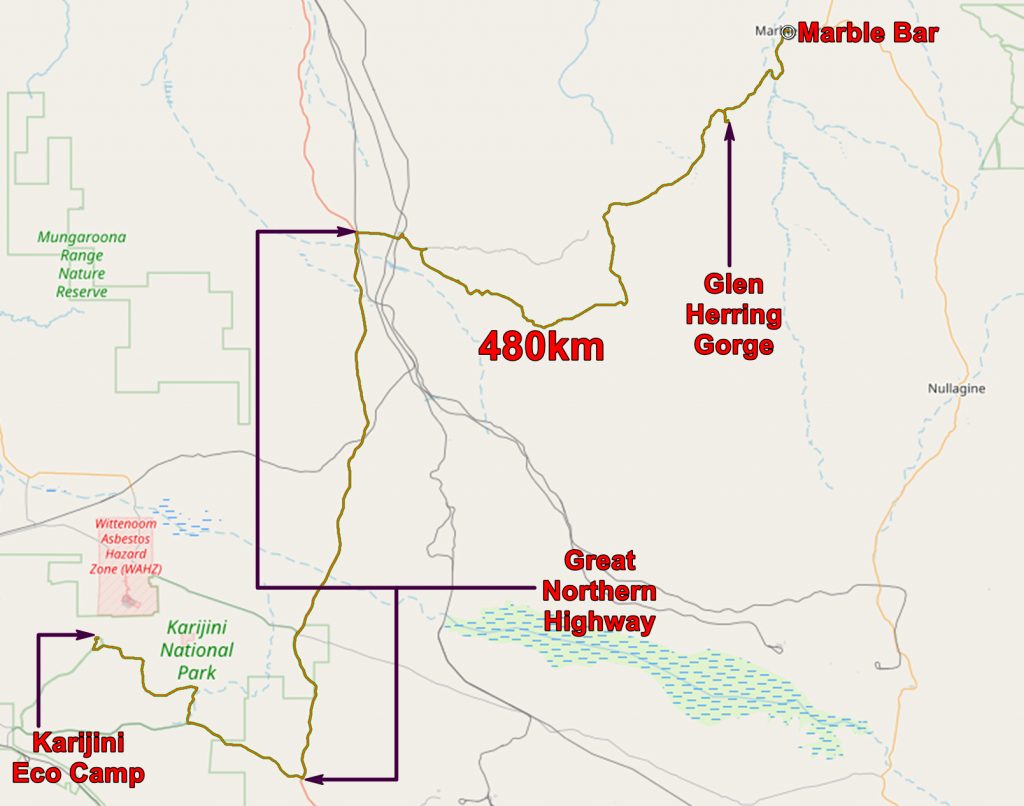

Did about 240 miles today, much along empty dirt roads after we turned off the Great Northern highway. The route from the highway to Marble Bar is featured in a publication of the Geological Survey of Western Australia called “Discovery Trails to Early Earth” by Martin Julian Van Kranendonk and J. F. Johnston (ISBN 1741682452, 9781741682458). A file, which can be opened with Google Earth, detailing the sites mentioned in the book, can be found HERE. Further information about the book can be got HERE. This latter link is probably the only place you can get the book from. At present the book can be downloaded as a PDF HERE.

Geology map of Marble Bar area, with our routes.

Once we left the highway our first geological stop was to look at a granite tor which was not far off the road.

A granite tor – part of the Yule Granitic Complex

Great batholiths of very ancient granite are characteristic of this part of the Pilbara. They are almost 3 billion years old and are easily seen on Google Earth.

Granites of the East Pilbara, with some other features of geologic interest.

The tors are the most prominent features in a flat landscape.

Granite tors

Up close they become much more interesting. They are a pile of huge almost spherical boulders with lots of interesting grottos between the boulders. Many have petroglyphs, although we did not see any.

Chris on one of the tors.

The next geologic excitement was when we came upon the Black Range dykes. there is one prominent one – labelled in the Google Earth extract above – but if you zoom in to the area you will find several others with the same trend. The next photos are of a relatively minor one, but even this is pretty big!

One of the Black Range dykes. It forms a linear ridge with blocks of dolerite running down its flanks.

The age of these dykes is considerable – 2.77 billion years. The amount of material in the dykes must be huge. The main dyke is 70 km long and 250 metres wide. They are thought to be the feeders for the Mount Roe Basalt at the base of the Fortescue Group.

A closer view of the dolerite dyke.

The injection of so much material up and along this dyke had a great influence at the tip of the crack formed by the injection of magma. Even a crack as big as this has to have an end and this is seen at our next stop.

This was where the road crosses a stream at the end of the Black Range. All of the dyke is south of this spot. The crack which allowed the magma injection ends here. And here there is an unusual conglomerate. The big blocks are rounded but the small fragments are angular. In a normal, water lain, conglomerate it would be the other way around. In a normal conglomerate the smaller fragments have been transported farther and therefore would be more rounded. There are some small rounded basalt pebbles present.

The conglomerate at the tip of the Black Range

It is thought that the conglomerate was formed as a result of the emplacement of the Black Range dyke. As it was injected into its fracture it grew a fracture in front of it. this would be full of hot gases from the dolerite, groundwater and granite boulders plucked from the sides of the fracture. The gases and groundwater would form high pressure steam which milled the boulders making them round. The milled fragments would be angular. At a late stage some basalt clasts entered the mix. Then it stopped and what was there consolidated into what we see now.

The unusual conglomerate. There are some basalt fragments, especially below the triangular boulder on the left. Note the chert on the middle right.

After a few more geological stops (including the not very interesting Glen Herring gorge) We continued to Marble Bar and got a powered site at the caravan park.

Tuesday 1st October 2013

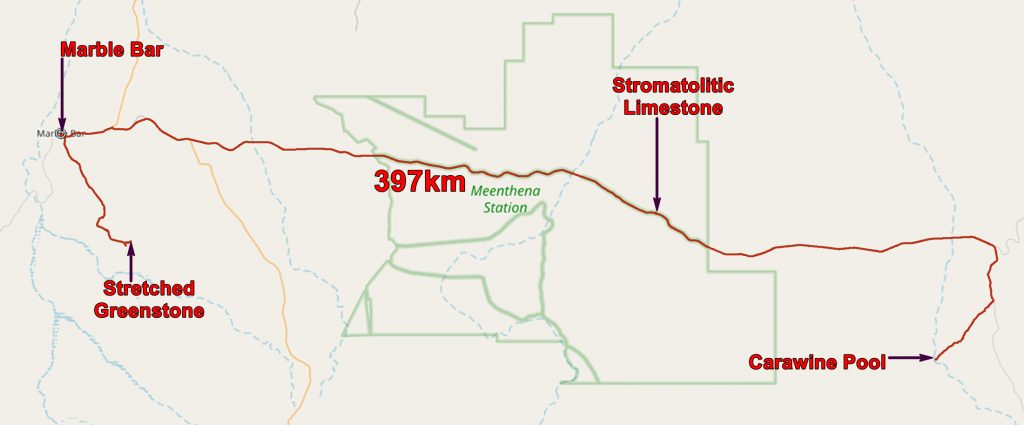

Today turned out to be a long drive but we did see some nice geology.

We started by going to the terrestrial equivalent of a black hole! This is in the Warrawoona Syncline, found between the Mount Edgar Granite and the Corunna Downs Granite. As these granite domes rose, the heavy greenstones, through which they rose, slid off the tops and down the sides. As the older rocks went down, the younger ones rose and, as a result the greenstones were stretched vertically. You can see the position of these unusual rocks in the Google Earth extract above.

Vertically stretched greenstone

These greenstones are not very green! In fact they are felsic volcanics (quartz rich lavas, probably) but the whole sequence in which they appear contain lots of more basic lavas, which weather green and these give their name to the whole.

A closer view of the stretched rocks.

Unlike a black hole this process did not go on for ever – it eventually froze preserving a very unusual rock.

These are very old rocks – 3.45 to 3.31 billion years old. the granites are not much younger – about 3.3 billion.

We then decided that we would like to go for a swim and decided that Carawine Pool was the place. We must have been blasé about distances by this stage the round trip distance between Marble Bar and the pool is about 235 miles! But it seemed a good idea at the time. And we did have the consolation of having our geological guide book to inform us of what we were passing through.

Geological map of our trip to Carawine Pool.

The highlight of the trip was a look at some stromatolitic limestone.

Stromatolitic limestone on the way to Carawine Pool.

This is part of the Tumbiana Formation which is about 2.72 billion years old. These were once thought to be the evidence for the earliest life on earth but, not far away, there exist stromatolites which are 3.4 billion years old. Dealing with such ancient rocks it takes a little thought to remember that there is 680 million years between the two!

While I was at the outcrop a road train passed by. It was carrying manganese from the Woodie Woodie mine to Port Hedland – a round trip distance of 465 miles. It is along tarred roads all the way but it still must be quite a job. It is slightly less than the distance from Bristol to Aberdeen. Seeing this shows how essential the railway from Newman to Port Hedland was. How many trucks per day would be required to get a quarter a million tons to the port?

Manganese road train on its way from Woodie Woodie to Port Hedland.

We pressed on and eventually got to Carawine Pool. As a swimming hole it was a bit of a disappointment. A recent flood had cleared a lot of the vegetation and deposited a vast quantity of gravel so it was a bit bleak. But there was a lot of water in the pool – it is actually a part of the Oakover River.

Carawine Pool

The rock on the other side of the pool is the Carawine Dolomite – 2.55 billion years old.

After our swim in the rather murky water we returned to Marble Bar and had a welcome drink in the Ironclad Hotel.

Wednesday 3rd October 2013

By this stage we had determined that we would be back in Perth on Saturday so we had long distances to cover. We would drive to Perth from Kalbarri. It would take one overnight stop to get there and there are few attractive places en route, so we decided to wild camp when the time and place looked right.

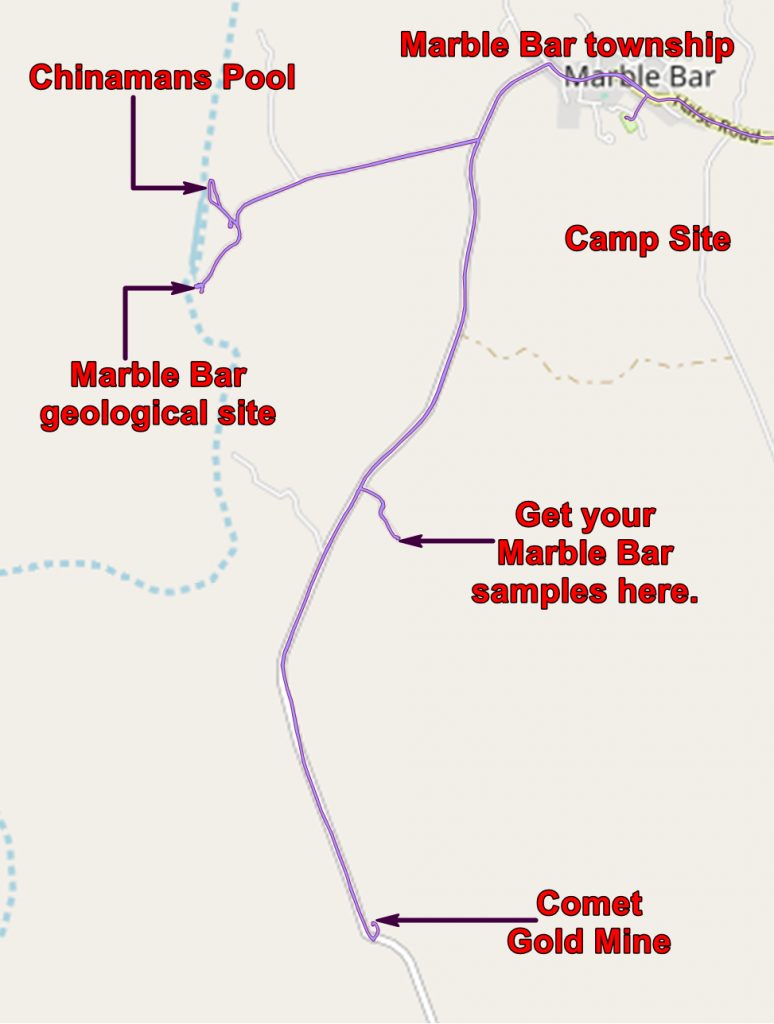

But first we needed to see THE “marble bar”. This bar across the local river is what gives the place its name.

Pelican at Chinamans Pool, close to the marble bar

The “marble bar”

The first Europeans to look at this knew a little about rocks and called them marble. Later people recognised them as being made of silica, not calcium carbonate and so called them chert. Red chert has a little haematite (iron oxide) as impurity and is called jasper. The blue-black chert has pyrite and carbonaceous impurities. Chert without impurities is white.

Chert showing regular banding

The bedding indicates that these were originally laid down as sediments. They have been tilted and are actually overturned.

Lots of jasper

The rocks may have started as sediments but that was not the end of the story. The sediment laid down was nothing like the rock we see now. It seems that they started out as a limestone! (So Marble Bar was not completely wrong!) Then silica bearing sea-water circulated into the crust, was heated up by the underlying granites and transformed the limestone to chert. It was not a passive process – the hot fluids returning to the surface, besides transforming the rock, fractured it. You can follow regularly banded chert into zones where it is broken and disrupted.

Regularly banded chert and fractured chert just above Chris’s toe.

More disrupted chert

You are not allowed to collect specimens at this site, so we drove along the strike to a spot where someone has dynamited some blocks off a cliff face and there we collected a nice specimen.

Then to the Comet Gold Mine which was once a very profitable venture but now exists as a purveyor of tourist stuff. Chris was hoping for a gold nugget pendant but settled for some jasper earrings. I got a T-shirt.

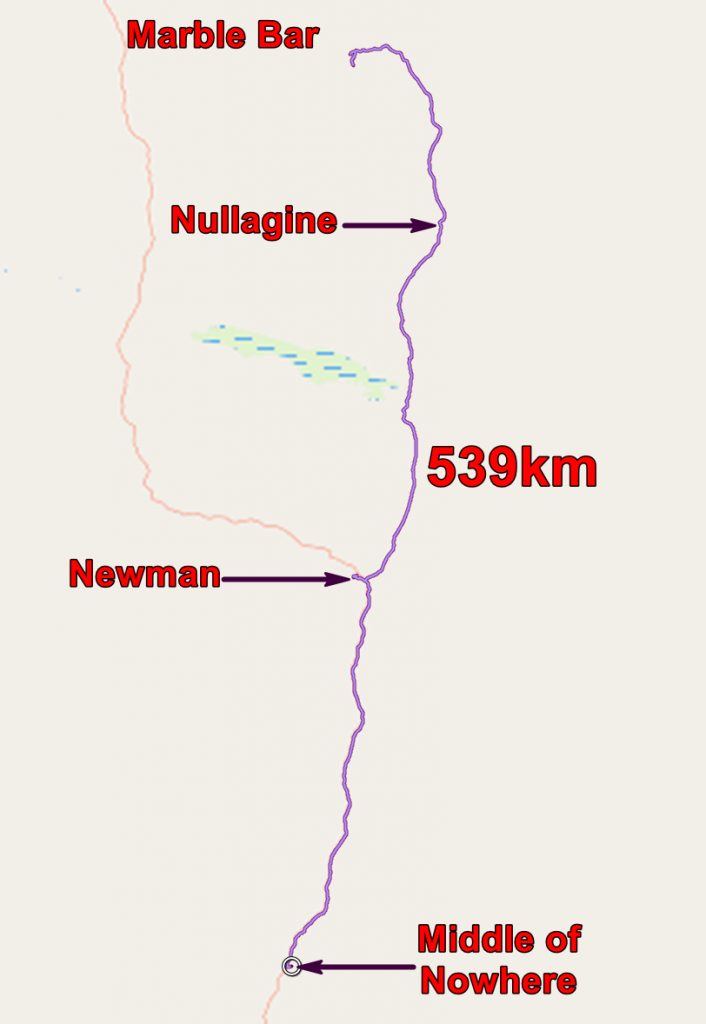

Then it was a long slog southwards. The road past Nullagine was dirt for most of the way. Nearer Newman it was tarred as there was a lot of mining activity. I think a new BHP iron ore mine is being developed here.

We did some shopping in Newman and continued on our way. In late afternoon we started looking for a suitable site for wild camping and eventually found a suitable spot a few hundred yards off a side road.

Chris at our wild camp site

The application below shows you various .kmz files. If you open them with Google Earth you will get our route and the photographs I took, at the spot I took them, displayed in all their glory! Download the file you want, store it somewhere on your computer, open Google Earth and open the file.

[slickr-flickr tag=”Marble Bar”]