We set off for Newman next morning with several objectives in mind:

- Refuel

- Fix Johns tyre

- Get some groceries

- Contact people in Perth and the UK

- Tour the Mount Whaleback iron ore mine

We managed to do all of that although John’s tyre had to be replaced – heavy trucks and dirt roads are not kind to flat tyres.

The Mine Tour was interesting and extremely safe. The mine is huge with lots of big machines but we were not able to get anywhere near them. Even so we had hard hats, visibility vests and safety goggles.

Chris and Graeme fully equipped for our bus tour.

Broken Hill Propriety (BHP) is turning Mount Whaleback into Lake Whaleback. They should achieve it in 60 years. They are mining haematite from the Banded Iron Formation rocks (BIFs) in particular the Brockman Iron Formation. These are iron rich sediments which have been further enriched in iron content by surface waters percolating down. These pick up iron from the overlying rocks and redeposit it in places, making the rock an economic ore. And the ore can be 70% iron! Anything below 50% Fe is considered waste. This contrasts with grades of less than 40% Fe which used to be mined at Corby in the East of England.

The bus took us up to a lookout high above all the mining activity from which lots of stuff was pointed out. The lady in charge certainly knew her stuff! She bombarded us with statistics and information emphasising the size of the operation. It soon became apparent that was as close as we were going to get to anything moving. Still we were able to see a lot. I’m glad I had my telephoto lens!

A part of the Mount Whaleback mine not being currently worked.

A busier part of the mine – people working at the left edge, just above the railing.

A close up of the “busy” part of the mine. Dumper trucks (240 tonners!) waiting to be loaded by a loader the top of which can be seen. Just in front can be seen vertical blast holes. These will be detonated to produce more broken rock to be loaded, processed and exported.

This was once a mountain. in 60 years or so it will be a rather deep lake.

Blast holes being drilled. They also allow the grade of iron ore to be measured so that, by selective mining, a consistent grade can be produced.

Ore trucks on their way to the processing mill.

This is where the mined ore is crushed, sized,sorted and prepared for shipping. On the left can be seen the train loader. The train goes through the hill and is loaded in the middle. The ore is supplied by the conveyor belt coming from the right.

Some indication of the size of the machines: Chris next to a used tyre from a dumper truck.

Back at the visitor centre we completed our tasks and got permits to drive along the road next to the railway taking ore to Port Hedland. Here it was just a formality. This not always so – RTZ at Mount Tom Price make a BIG DEAL about it.

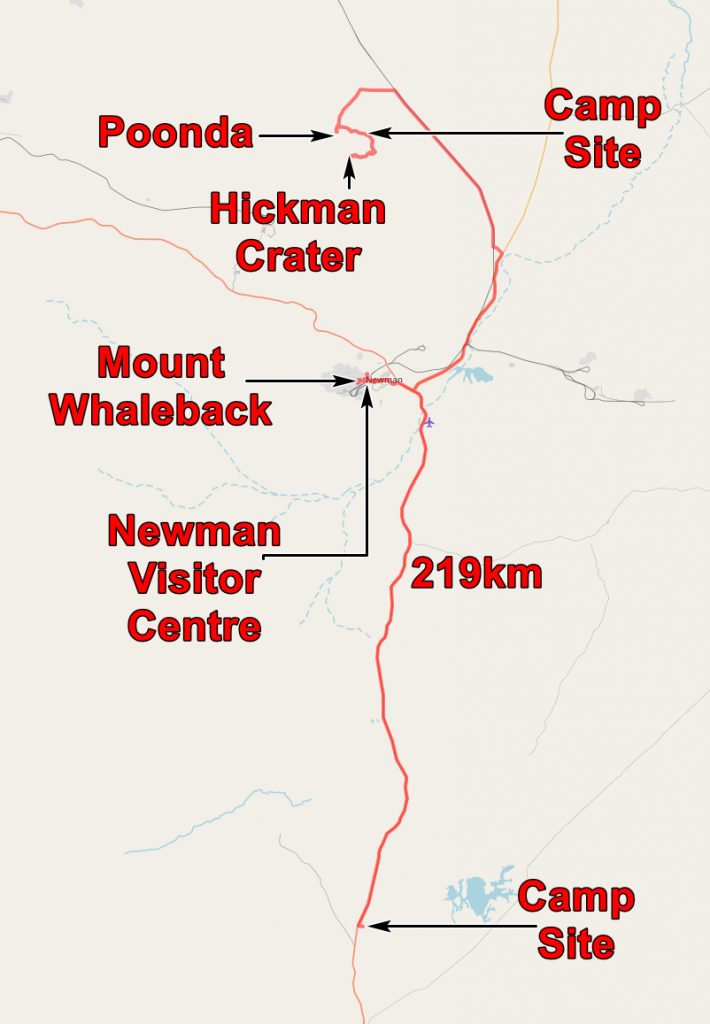

At Poondal Siding we headed south and after driving along bad tracks came to the Punda aboriginal art site. Here the petroglyphs are on dolerite boulders which are scattered over the hillside.

Julie at the Punda Aboriginal Art site

Aboriginal art at Punda

Aboriginal art at Punda

Aboriginal Art at Punda

I must admit Aboriginal Art does not do much for me, but lots of people tell me that I am wrong. I don’t like graffiti either, so perhaps I am doomed.

We then set off for the Hickman Crater. This was discovered in 2006 by Arthur Hickman, a senior geologist with the Western Australian Geological Survey. He found it when browsing Google Earth preparatory for heading into the bush and he saw this:-

Later site visits confirmed that it was an impact crater. It is interpreted as a meteorite striking a valley side. The open side of the crater was valley and here the debris was flung across the valley and did not leave the crater edge seen on the other sides.

The name of the crater has not been settled as it not acceptable to name a feature after a living person, but I am sure a suitable name will emerge.

Hickman Crater – the open side and the crater walls.

The crater walls

After rummaging about the crater floor looking for meteorite bits, we set off to find a place to camp.

And found the best camp site of our trip.

Our best wild camp site

We reckoned there was no one within twenty miles of us – it was certainly very quiet.

The application below shows you various .kmz files. If you open them with Google Earth you will get our route and the photographs I took, at the spot I took them, displayed in all their glory! Download the file you want, store it somewhere on your computer, open Google Earth and open the file.

If you don’t have Google Earth you can get it HERE.

[slickr-flickr tag=”14-08-13″]